Effect of different types of exercise on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women

Menopause is an inevitable physiological stage in a woman’s life. It is accompanied by a series of hormonal changes, foremost among which is a drop in estrogen levels. This change not only affects reproductive functions, but also has profound consequences for bone health. Estrogen deficiency leads to accelerated bone remodeling in favor of resorption, increased osteoclast activity, and a relative decrease in bone formation by osteoblasts. As a result, bone mass gradually decreases, exposing menopausal women to an increased risk of osteoporosis and fractures.

In 2019, approximately 32 million people in Europe were affected by osteoporosis, including 25.5 million women and 6.5 million men, representing approximately 22% of women over the age of 50. It is estimated that after the age of 65, half of all women are affected. The resulting fractures (particularly hip fractures) are associated with high morbidity and mortality. One in five women dies within a year of a hip fracture, and half of those who survive are left with disabling sequelae. Globally, the projections are alarming: by 2050, an estimated 4.5 million hip fractures will occur each year. Beyond the individual tragedies, the economic and social cost of these fractures represents a considerable burden on healthcare systems.

Preventing osteoporosis and preserving bone mineral density are therefore a priority. Among non-pharmacological interventions, physical exercise plays a central role. It is known to stimulate bone metabolism, improve muscle mass, strengthen balance, and reduce the risk of falls. But are all forms of exercise equally beneficial? Should we focus on high-impact exercises, weight training, endurance activities, gentle activities such as Tai Chi, yoga or Pilates, or even more “exotic” methods such as exercises on a vibration platform?

The study

To answer these questions, Chinese researchers conducted a systematic review followed by a meta-analysis. To do this, they analyzed 49 studies that compared different types of exercise in randomized controlled trials. In total, 3,360 women who had been menopausal for more than a year before the start of the studies and had an average age of 61 were represented.

The physical activities tested were grouped into eight categories:

The control group varied depending on the study: no intervention, usual care, or general lifestyle advice. The main criteria analyzed were bone mineral density of the lumbar spine and femoral neck, measured by densitometry. The duration of the interventions ranged from 2 to 72 months, with an average of about 12 months, for an average frequency of three sessions per week (1 to 7 sessions per week depending on the study).

Results & Analysis

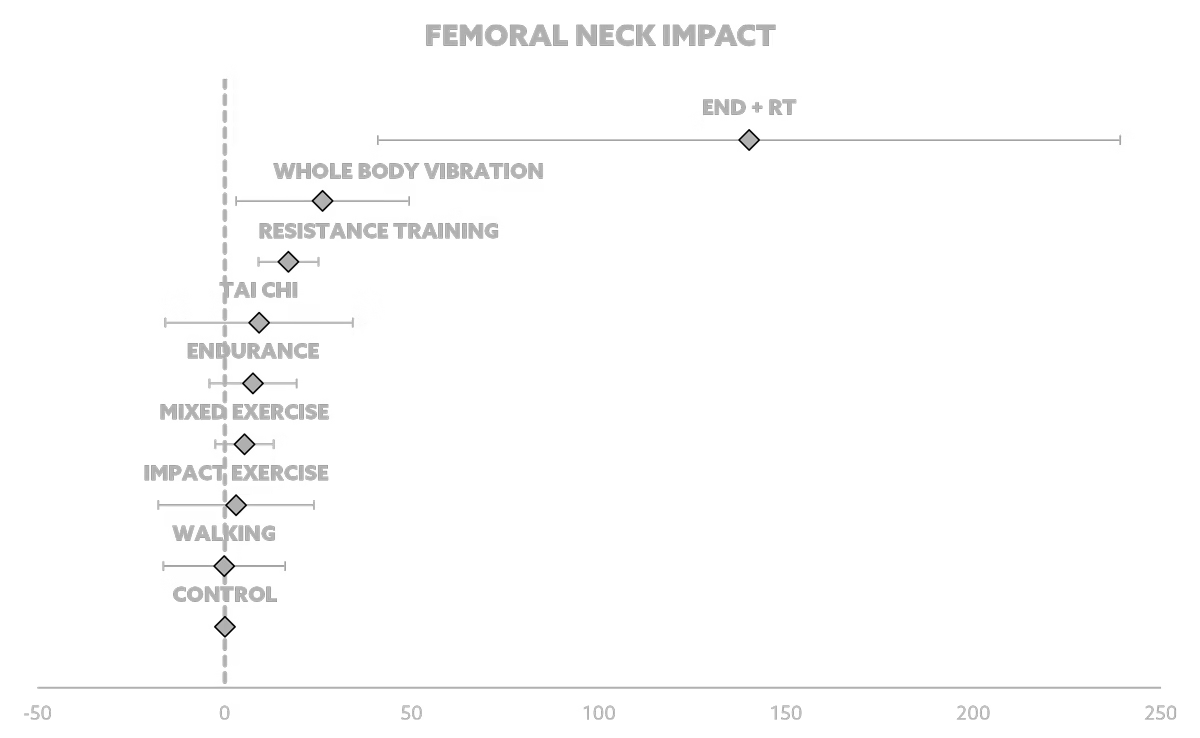

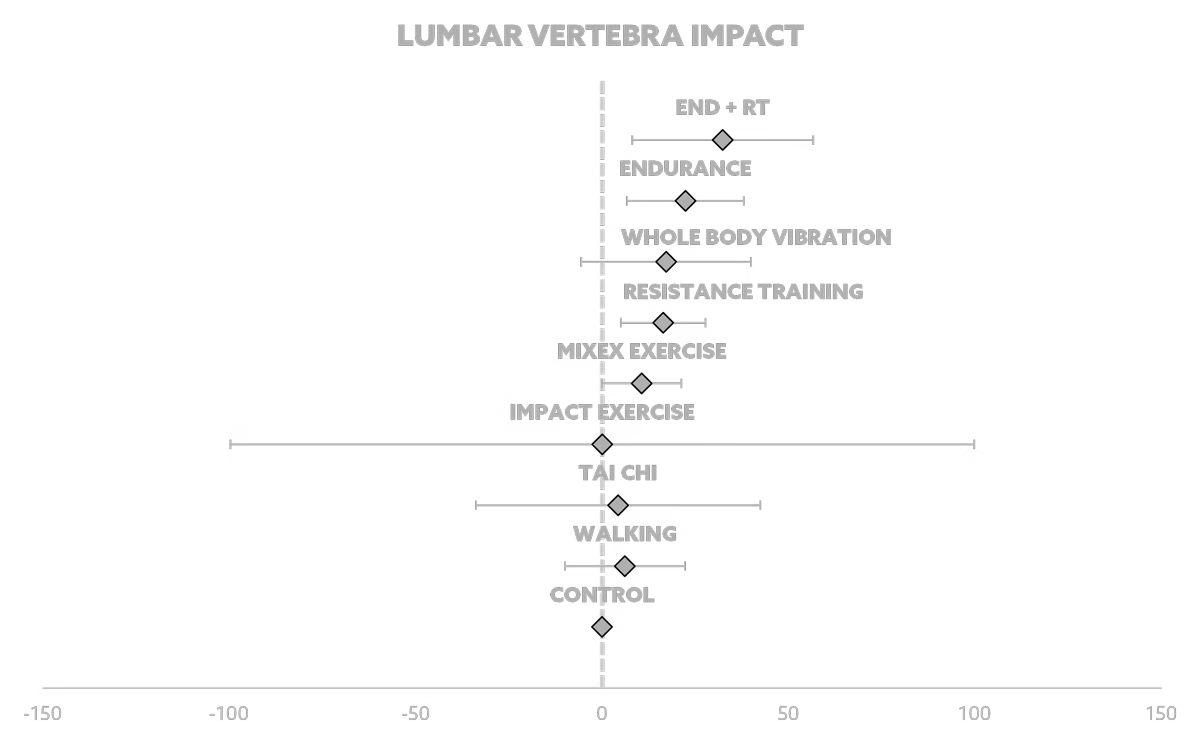

The main results of this study are clear: physical exercise significantly improves lumbar and femoral bone mineral density in postmenopausal women. However, the extent of the effect varies depending on the type of intervention. In the lumbar spine, the combination of endurance and strength training came out on top, followed by endurance training alone, then whole-body vibration and strength training alone. All of these practices showed a significant positive effect compared to the control group.

In the femoral neck, the results are slightly different. Here again, the combination of endurance and strength training dominates, followed this time by whole-body vibration, then strength training alone. The other modalities (Tai Chi, mixed exercises, impact exercises, or walking) did not show statistically significant effectiveness.

The combination of endurance and strength training combines several complementary mechanisms. Endurance improves bone vascularization, favorably modulates certain hormones, and reduces osteoclastic activity. Strength training, on the other hand, applies direct mechanical stress to the skeleton, stimulating bone formation by activating osteoblasts. Together, these two modalities act synergistically on bone remodeling.

Whole-body vibration is a special case. This approach, which is still under debate, involves subjecting the body to small mechanical oscillations via a vibrating platform. Several animal and human studies suggest a beneficial effect on femoral neck density without requiring intense muscular effort. The exact mechanisms remain under discussion, but the hypothesis is that vibrations induce subtle mechanical stimulation that activates bone cells. The benefits are obvious for frail or immobile elderly people, for whom intensive exercise is difficult. However, the variability of protocols (frequency, duration, intensity of vibrations) calls for caution in drawing conclusions.

These results confirm that exercise is a powerful lever but that it must be chosen wisely. Simply walking or practicing Tai Chi, although beneficial for other health parameters (balance, mobility, relaxation), is not sufficient to significantly preserve postmenopausal bone density. On the other hand, programs combining endurance and strength training, or incorporating specific mechanical vibrations, appear to be the most promising.

Finally, it is important to highlight the methodological limitations of the analysis. The heterogeneous quality of the trials, the diversity of intervention durations and intensities, and the lack of standardization complicate interpretation. In addition, most participants were relatively young and in good health: the results cannot necessarily be extrapolated to very elderly, frail women or those with severe osteoporosis.

Practical applications

What should we take away from this? First, physical exercise should be systematically recommended to postmenopausal women, not only for bone health, but also for the overall cardiovascular, metabolic, and psychological benefits it provides. However, not all forms of exercise are equal in terms of bone health.

Priority should be given to programs that combine endurance and strength training. In practical terms, this can translate into two to three weekly strength training sessions, combined with regular endurance training (running, cycling, rowing). Strength training should include progressive loads that are heavy enough to mechanically stimulate the bone.

Whole-body vibration could be an alternative or a complement, especially for frail women or those with physical limitations. However, this method still needs to be standardized before it can be widely incorporated into recommendations.

Exercises such as Tai Chi and walking should not be ruled out: they provide other major benefits (balance, mobility, cardiovascular health) and can be a gateway to more structured activity. However, they are not sufficient on their own to preserve bone density.

Menopause is accompanied by accelerated bone loss, which increases the risk of osteoporosis and fractures. While physical exercise is a powerful preventive strategy, its effectiveness depends on the type of exercise. According to this meta-analysis, the combination of endurance and strength training is the most effective for preserving lumbar and femoral bone mineral density. These results should encourage all women to get moving, but above all to incorporate structured training combining resistance and endurance as early as possible in life. It is in this synergy that the best bone protection lies and, beyond that, a means of preserving autonomy, quality of life, and longevity.

Reference

Xiaoya, L., Junpeng, Z., Li, X., Haoyang, Z., Xueying, F., & Yu, W. (2025). Effect of different types of exercise on bone mineral density in postmenopausal women: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Scientific Reports, 15(1), 11740.